This article is more than 1 year old

Swots explain how to swat CPU SNITCHES

Side-channel attacks are real because CPU leakage reveals instructions being executed

A variety of sneaky side-channel attacks have been demonstrated over the years: from measuring the amount of processor power devoted to encryption to using an antenna to pick up stray electromagnetic emissions from computers.

Myth-of-recency headlines aside, learning what a computer is doing by listening to its electronics has been demonstrated in academic research for at least a decade (here, for example, is a story from 2004).

Hacker-boffins from Georgia Tech have offered up a technique to measure the electronic side-channel attack risk in a particular environment.

The aim, the study says, is to help find ways to protect against electromagnetic noise as a side-channel attack by discovering “the most vulnerable aspects of a processor architecture or program”.

In this paper, to be delivered to the upcoming IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Microarchitecture in Blighty, Robert Callan, Alenka Zajic, and Milos Prvulovic propose and demonstrate what they call "Signal Available to Attacker" (SAVAT) as a metric that can help quantify the risk posed by stray emissions.

The researchers tested three different laptops – one with a Pentium M processor, one with a Core 2, and the third with an AMD Turion X2 – and watched for differences in electromagnetic emissions for 11 different instructions.

The choice of processors gave the study a variety of cache architectures, important because cache operations are among the functions the side-channel tests used. The Core 2 Duo has a 32 KB 8-way level 1 cache and a 4096 KB, 16-way level 2 cache; the Pentium 3M has a 16 KB, 4-way level 1 and 512 KB, 8-way level 2 cache; and the Turion X2 has a 64 KB, 2-way level 1 and 1024 KB, 16-way level 2 cache.

On-chip instructions, they found, generate less noise than instructions that involve off-chip calls (for example, to memory), and that “particular instructions, such as integer divide, have much higher SAVAT than other instructions in the same general category (integer arithmetic), and that last-level-cache hits and misses have similar (high) SAVAT.”

The researchers note that “the difficulty with which an attacker can obtain the secret information depends on both 1) program activity: the information-dependent difference created at the instruction level, and 2) the side channel signal’s dependence on these instruction-level differences.”

Other work, such as the Side-Channel Vulnerability Factor (SVF, described in this PDF) have looked at program activity; the SAVAT metric is designed to measure how the side channel signal reveals “instruction-level differences”.

The measurement is “pair-wise” – that is, it reflects the differences in side-channel signal available to an attacker “when we execute instruction/event A instead of executing instruction/event B (or vice versa).”

The 11 instructions tested covered main memory load/store; cache load/store (both levels), adding and subtracting values from the register, integer multiplication and division, and a null instruction event.

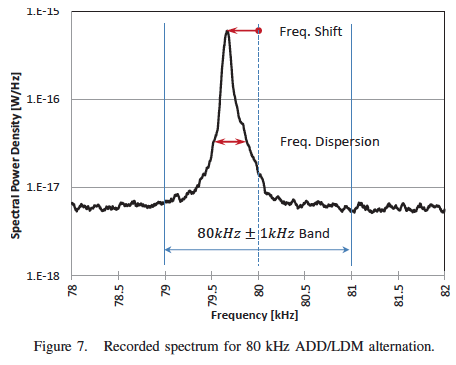

As the image below shows, there are clear signatures for such operations.

The noise signature of some instructions is unmistakeable.

As already stated, the aim of this study is to look at what's already known about side-channel noise, and look for mitigations. Among many other things, the researchers conclude:

“[T]he path of least resistance for the attackers is in code that uses off-chip accesses, L2 cache accesses, and possibly DIV instructions in ways that depend on sensitive data, so the architects’ focus should be on making execution of these instructions less EM-noisy, e.g. through limited use of compensating-activity techniques.

“For programmers, these results confirm what programmers should already know from work on other side channels - in code that processes sensitive data, special care should be taken to avoid situations where a memory access instruction might have an L2 hit or miss depending on the value of some sensitive data item.”

Further: “at short distances particular instructions, such as the integer divide, have much higher SAVAT than other instructions in the same general category (integer arithmetic), and that last-level-cache hits and misses have similar (high) SAVAT.”

Previous side-channel work reported by The Register can be found here, here, and here, among many other examples. ®